Of Lectures and Lyceums

- Home

- About Salem »

- Salem Tales »

- Of Lectures and Lyceums

Of Lectures and Lyceums

The Salem Lyceum Society

It is unlikely that any American movement has permeated the national culture as quickly and thoroughly as the lyceums in the mid-nineteenth century.

Lyceums were the brainchild of Joshua Holbrook, who borrowed the concept from the Mechanics Institutes he had encountered in England. Holbrook started the first lyceum in Milbury, Mass., in 1828 and before long there were 100 similar societies sprinkled throughout New England. By 1834, the number of lyceums in America had grown to 3,000.

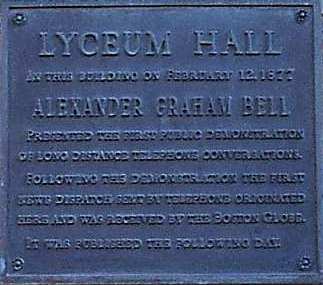

The Lyceum Hall on Church Street

One of those lyceums was organized in Salem in January 1830. The expressed purpose of the Salem Lyceum Society was to provide “mutual education and rational entertainment” for both its membership and the general public through a biannual course of lectures, debates and dramatic readings.

While no debates were actually ever held, there were, over the next 60 years, more than 1,000 lectures on such varied themes as literature, science, politics and government, and even phrenology. The inaugural lecture, “Advantages of Knowledge,” was given in February by Society President Daniel White, and followed by talks by Society Treasurer Francis Peabody, and Society Vice President Stephen C. Phillips and others. James Flint concluded this first course with three lectures on anatomy and health.

These early lectures were held in either the former Methodist Church on Sewall Street or the Universalist Church on Rust Street. In 1831, the Salem Lyceum Society bought land and erected its own building on Church Street at a cost of approximately $4,000. The new hall could accommodate 700 patrons in amphitheater-style seating and was decorated with images of Cicero, Demosthenes and other great orators of bygone days.

Lectures were held on Tuesday evenings. Admission was $1 for men and 75 cents for women, who had to be “introduced” by a male to gain entrance. Most of the early speakers, including John Pickering, Henry K. Oliver and Charles Upham, were Lyceum members and spoke gratis or for a minimal fee. The combination of unpaid lecturers and sellout crowds (most talks had to be repeated on Wednesday) enabled the Society to pay off the outstanding mortgage on its new hall in a short time.

Once free of its overhead, The Salem Lyceum Society could afford to bring in outside speakers and, over the next half century, many of the great intellects of New England found their way to the Church Street stage. Richard Henry Dana Jr. spoke on “The Reality of the Sea” and “The Importance of Cultivating the Affections,” while former United States President John Quincy Adams related themes of “Faith and Government”. Oliver Wendall Holmes discoursed on “Lyceums and Lyceum Lectures;” abolitionist Frederic Douglas, on “Assassination and its Lessons” shortly after President Lincoln’s murder; and James Russell Lowell, on “Dante.”

Once free of its overhead, The Salem Lyceum Society could afford to bring in outside speakers and, over the next half century, many of the great intellects of New England found their way to the Church Street stage. Richard Henry Dana Jr. spoke on “The Reality of the Sea” and “The Importance of Cultivating the Affections,” while former United States President John Quincy Adams related themes of “Faith and Government”. Oliver Wendall Holmes discoursed on “Lyceums and Lyceum Lectures;” abolitionist Frederic Douglas, on “Assassination and its Lessons” shortly after President Lincoln’s murder; and James Russell Lowell, on “Dante.”

Salem’s most famous personage, Nathaniel Hawthorne, never spoke at the Lyceum himself but, during his stint as corresponding secretary for the 1848-9 lecture series, he enlisted as lecturers many of his famous associates. Hawthorne’s roster of speakers included his brother-in-law, Horace Mann, his Concord friends, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, and his publisher, James T. Fields. Hawthorne was also responsible for the largest fee ever paid to a guest lecturer: Daniel Webster walked away with a cool $100 for his talk on “The History of the Constitution of the United States.”

The record for the most appearances unquestionably belonged to Emerson, who spoke nearly 30 times in the Salem Lyceum alone. Like many other authors of the era, Emerson used Lyceum audiences to gauge the popularity of an essay or book before going to the expense of publishing it.

Over the life of The Salem Lyceum, only a half-dozen women were invited to appear on the Church Street stage. The best known was British actress Fanny Kemble, whose dramatic reading of Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, was a highlight of the 1849-50 course of lectures.

One of Kemble’s fellow female presenters bore the appropriately Victorian name of Laura F. Dainty.

Ironically, the most significant event to take place in the Lyceum Hall – Alexander Graham Bell’s first public demonstration of the telephone on February 12, 1877 – was sponsored not by the Salem Lyceum Society, but by the Essex Institute.

But in the lyceum tradition, the event proved so successful and popular that it had to be repeated a few weeks later.

Jim McAllister

All rights reserved